From Conservationist to Ag Biotech Entrepreneur

After taking a winding journey through scenes of environmental degradation on three continents, Eli Hornstein decided to reach beyond his career as a conservationist to make a bigger difference in sustainable development by working in agriculture.

He returned from a Fulbright scholarship in Mongolia to earn a Ph.D. from North Carolina State University’s Department of Plant and Microbial Biology before taking on one of the biggest challenges to sustainability of all: climate change.

Through his startup company Elysia Creative Biology, he’s hoping to commercialize crop plants genetically engineered to practically eliminate methane emissions from cows that eat them.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas responsible for almost a quarter of climate change, and agriculture — including cows and similar livestock — is its second biggest source.

Lots of plant chemicals do a very good job suppressing methane. … But they’re expensive. They’re hard to produce.

Using proprietary technology, Elysia has genetically engineered feed crops to produce compounds that suppress methane from cows and other ruminants, such as sheep and goats. Hornstein’s goal is to get farmers and companies who produce grain and pasture for animal feed to begin using his engineered seeds.

“Lots of plant chemicals do a very good job suppressing methane. They might come from seaweed, or they can be found in garlic or orange peels. But they’re expensive. They’re hard to produce,” Hornstein says.

“But what we are talking about is getting existing feed crops to produce these compounds. We’re offering farmers a product that looks just like what they’ve always been using, and it doesn’t require them to make a huge change in how they run their farms.”

A Passion for People and the Environment

How did Hornstein get from the field of conservation to climate change and cattle? It began with a commitment to people and the environment, he says.

Having grown up in Raleigh, Hornstein spent part of his childhood in Eritrea, in sub-Saharan Africa, where his parents taught at the University of Asmara.

“That was really the start of my personal exposure to the broader world and to the desire to want to improve the environmental situation at a global level, especially for people who have been disadvantaged by the past and are now on the receiving end of some of the world’s biggest problems.”

Determined to be a conservationist, he simultaneously attended Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as an undergraduate on the Robertson Scholarship, earning degrees in linguistics and biology. He went on to do conservation work in Panama, Costa Rica, Kenya, and finally Mongolia, where he was a Fulbright Fellow.

During a trek through remote mountain areas from Mongolia to Southeast Asia, he decided there were faster and perhaps better ways to get the kind of world he wanted.

“My goal was to observe firsthand the effects of climate change on some parts of the world that we like to imagine are among the least-developed and most pristine,” he recalls. “My expectation was to find that these areas remain relatively stable for the time being.”

What he found surprised him.

“The trip started out with unprecedented flooding in Ulaanbaatar that brought the capital of what is ordinarily a desert nation to a standstill and ended with such extraordinary heat in Chongqing (in southwestern China) that I saw panda bears fainting from the temperature,” he adds.

Changing Course

What Hornstein saw changed his trajectory.

“This experience quite early in my career is one I returned to as I formulated the conviction … that we must address climate change at the source, rather than adventuring off in search of some last imagined refuges from it,” he says. “I came to the realization that as conservationists, we will not succeed in protecting the environment by going out in the field to establish some park or program if we don’t also address these issues at the source, which is our need to use land and resources to take care of Earth’s human population.”

“To have an impact at the scale I wanted, I needed to work within agriculture to bring these pressures into balance and, in particular, in agricultural biotechnology, which has shown the ability to create rapid change in a system that is complicated and often slow-moving.”

Hornstein chose agriculture because almost half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture and the need for a growing supply of food to feed an increasing world population puts increased pressure on remaining natural areas.

And he chose biotechnology because he saw good in what it’s done for agriculture. “My observation was that biotech has a history within agriculture of rapidly creating change,” he says. “Engineered crops get adopted very quickly when people want them.”

But before he could enter the field of biotechnology, Hornstein knew he needed training and credentials. That led him to NC State, which was not only his mom’s alma mater, but also what he considered to be “the best place to learn how to be an agricultural genetic engineer.”

Methane … is purely a byproduct. We can get rid of it without hurting anyone’s livelihood or changing what food is available.

During his Ph.D. studies in Professor Heike Sederoff’s Plant Metabolic Engineering Lab, Hornstein focused on the plant microbiome and ways to reduce fertilizer needs. He gained skills with tools and techniques used in biotechnology and went on to use them as a postdoc at NC State.

While a postdoc, he’d heard about the role of agriculture in methane emissions, and he decided to see if he could come up with a biotech solution.

“The interesting thing about methane is that we don’t need it to have animal agriculture. It’s purely a byproduct. We can get rid of it without hurting anyone’s livelihood or changing what food is available to anyone,” Hornstein says. “And if we can really eliminate it without changing the productivity of those farms in a stroke, we can cut agriculture’s carbon footprint. That’s a huge win for the climate.”

Elysia’s early trials in 2023 showed promising results. Plants were producing a large amount of the first methane suppressor the company had engineered in, and lab animals that fed on them saw their methane emissions drop 90% in just a few days.

“That was enough for me to believe that we should start taking the next steps on moving the technology ahead and building a company that could get it out into the world,” he says.

Entering NC State’s Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

While Hornstein started Elysia in Durham, he returned to NC State University when he joined what’s now known as the N.C. Plant Sciences’ Seed2Grow program.

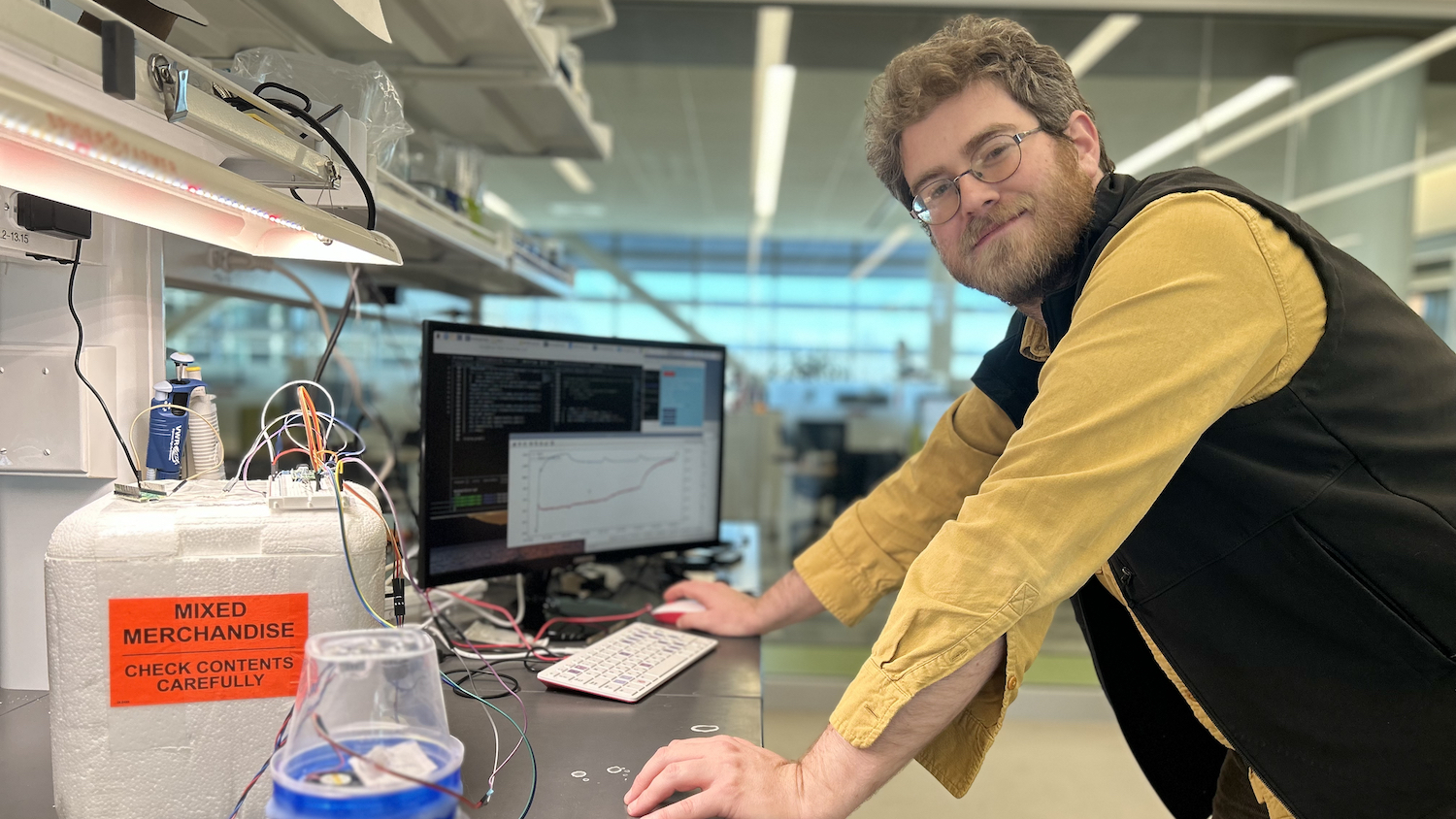

His company occupies space in NC State’s Plant Sciences Building on Centennial Campus, and he says he benefits from being near the university’s talented students and researchers, as well as its programs designed to help budding entrepreneurs like him succeed.

“The thing that was missing in our former space was the ability to do advanced work with plants. As an early-stage company, what we saw was almost nowhere offered you the facilities that are tailored to the type of work we needed to do,” he says.

“We didn’t just need PCR machines and incubators, we needed greenhouses and sequencing and analysis centers that know how to work with plant samples. All those things are right here in the Plant Sciences Building.”

What you want is not just facilities but relationships.

Hornstein says being at NC State also “gives me a way to keep meeting with professors and see new research that is coming out. When you are starting out in private industry, you don’t know how much of a wall can be there between new science and private work. Being here breaks down that wall.”

Hornstein has also found other NC State programs beneficial, including the National Science Foundation’s regional I-Corps training program, which is offered through NC State’s Office of Research Commercialization. It helps researchers transition their ideas and inventions into the marketplace through consumer discovery and market research.

Another helpful program, he says, was NC State’s Miller Fellowship, which provided for a stipend and new venture support to recent graduates who want to pursue building a strartup full-time but wouldn’t otherwise have the means to.

“If you’re someone like me who has a company and a technology, but you need the resources and community to really help develop it and keep it going, take advantage of some of the existing entrepreneurship programs at NC State to build your bridge and let that relationship try to grow a bit organically,” he says. “What you want is not just facilities but relationships.”

Next Steps

So far, Hornstein is positive about Elysia’s progress. Lab studies are promising, and in early July, he and Elysia were awarded the prestigious Activate Fellowship. The fellowship provides early-stage science entrepreneurs with significant funding, technical resources and other support.

Hornstein says it’ll be a few years before the company has customers, and there are important milestones to cross in technology and regulation. Next steps include securing additional funding for a farm trial, which involves putting Elysia’s techology in a common corn variety and measuring emissions from cattle in a real-world setting.

“In early tests, we see a positive effect that tells us that once we cross these hurdles, we really expect to find a lot of success on the other side.”

NOTE: Seed2Grow, the North Carolina Plant Sciences Initiative’s startup program, is accepting applications. For info, contact N.C. PSI Director of Innovation Partnerships Kathleen Denya.

This post was originally published in College of Agriculture and Life Sciences News.